‘…the less said about it the better’: the wisdom of shutting up about adventures and why I am still thinking about it.

Inconclusive ramblings asking why we need to talk about our adventures.

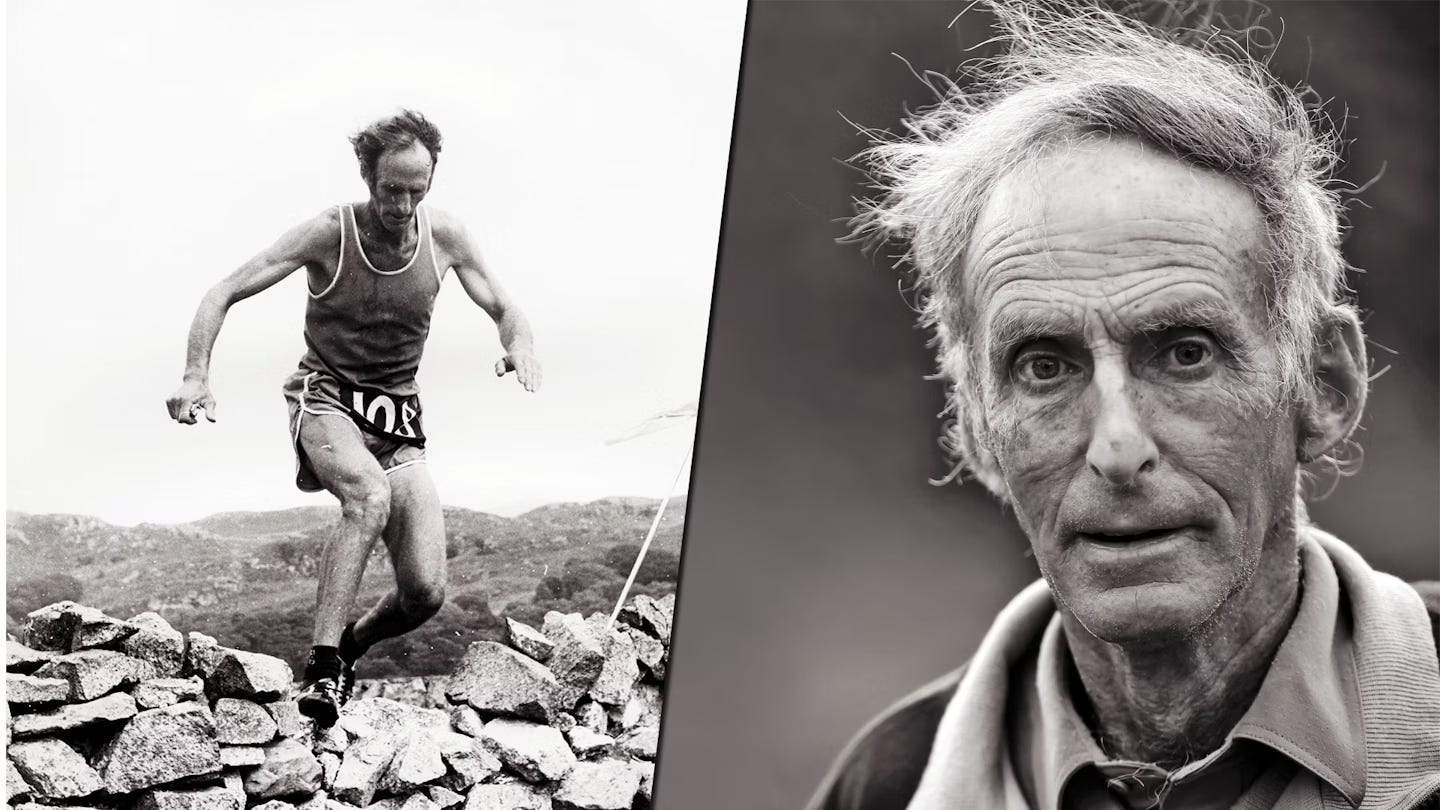

There’s a video clip of fell runner Joss Naylor being interviewed by the Guardian about some of his life long achievements in the short documentary King of the Fells, released shortly after his death in 2024 that I can’t stop thinking about.

Blink and you’ll miss it, but right at the very end of the 16 minute film, we see Joss, alone in a room, a frayed cap and jumper, still mildly uncomfortable and much older than the sprightly footage from the 70s and 80s we see earlier in the film. He’s mid sentence as the camera focuses on his face, lined, hollow and with paper-thin skin.

‘It’s just something you do. No it weren’t no big shaker, owt like that you know. No. It’s one of them things that you know, you has to do, and you go along and you do your best and you don’t tell anybody about these things unless they want to know.’

The interviewer asks, ‘so you let other people talk about them?’

‘Aye, aye,’ Joss answers, ‘it’s better that way int it? Aye.’

‘That’s very modest,’

‘Well, I don’t know about that,’ he says softly and with the smallest laughs, ‘it’s that the less said about it the better, int it’.

I must have watched this clip a hundred times, infatuated by this small glimmer of wisdom in an aged fell runner and farmer. I’m certain that this approach is what kept Joss running all those distances for 50 years, and I am equally certain that many people still assume that he’s speaking these words somewhat falsely. How can you possibly achieve all of the countless things that Joss Naylor has completed and have no inclination to speak of it?

‘The less said about it the better’.

In some ways, his sentiment is somewhat marred by the fact that he has spent - whether reluctantly or not - many years talking about his achievements. But that, surely, is just because people have asked? Regardless, there are other sportsmen and women who have echoed a similar sentiment over the years and haven’t spoken much about it. Beryl Burton for one, who to this day is still considered one of the strongest female cyclists of the 20th century and whose records still stand, rather famously eschewed sponsors in favour of remaining an amateur and working full time on a rhubarb farm. Her daughter Denise Burton-Cole remembered that she would never ‘brag’ but would just be ‘pleased and proud’ of her own achievements. After (usually) winning and toppling records, she would return to work the next morning as if nothing had happened. That’s pretty fuckin rad.

But why is it rad? This quality of ‘saying owt’ and getting on with, I have long admired in others. To be able to completely reject external validation and rely entirely on your own internal sense of accomplishment seems testament to a wonderfully resilient mental framework in my books. Where can someone get a sense of self-assuredness like that in today’s modern age of availability, comparison and perpetual betterment (eurgh)? After recently breaking my ankle, I received a text from a very well meaning friend who said that while I was convalescing, I could ‘focus on myself’ and take up a few courses or hobbies to get better at X or Y. Good god woman, I wanted to cry, I’m regrowing a bone all by myself, isn’t that enough self improvement for one day? The idea of spending my sudden free time working on improving, hustling, becoming a better version of myself to unveil to the world literally fills me with meteoric dread.

Anyway, I digress.

I have made some movement towards this stoic attitude. Many years ago I consciously uncoupled myself from Strava, realising that I had accidentally fallen into a vicious loop of stat one-upmanship with myself that was doing a rather good job at ironically making me much slower and weaker. It turned out that I was quite good at punishing myself for any and all transgressions from the impossibly high standards I had cultivated - entirely arbitrarily I might add. This was a helpful move. It allowed me to focus on much more interesting aspects of the running and cycling that I was doing. When the pressure of everyone I knew ‘seeing’ (and in my head ‘judging’) my stats on whatever ride or run disappeared, and when I could choose who to share that information with myself - personally and privately - I realised I altered the kind of trips I wanted to partake in.

Later, this led to a commitment that I would never never, ever share (unless it was specifically relevant) the distance or speeds of any of my rides or runs on social media. And I have maintained that commitment. Not that I do anything particularly spectacular or worthy of note anyway, but I began to feel that there were so many more interesting stories to tell about my adventures that have absolutely nothing to do with how far or how fast I went. And personally, even in world record attempts or in huge feats of athletic ability, it’s not those stats we care about is it? Not really. We want to know how that athlete felt, or is feeling, or what they saw, or thought. That’s why I was watching a short film on Joss Naylor in the first place.

I wonder whether some of this was reflected in Joss’s thoughts. In 1975, he managed to summit 72 peaks in the Lake District in 23 hours and 20 minutes, covering 38,000 feet of elevation and over 100 miles of technical terrain. Despite repeated attempts, this record stood until 1988, and is still considered an incredible performance of endurance. In interviews of the 1970s, he makes it clear that his running was guided by an interest in his own body and a love for being out in the hills - what would saying more have done to improve his record other than to satisfy the interests of others? He was clear that his experiences were his own.

And in some ways I recognise this in myself. Following a big trip or a huge achievement, I often find that I jealously guard that experience for some time. Sharing it, even with close friends, feels thorny and unwieldy, and I enjoy languishing in my thoughts until I can get a pair of gloves on and grip the body of them tightly. I can see why Joss and Beryl and any others might not have wanted to share. Your time outside with your body feels extraordinarily personal, because it is.

Nowadays, we’re all too connected to each other. The social media companies and oligarchs that make money off your data have made you feel that the right to complete privacy is an exclusive luxury that you don’t have and can’t afford. We’re all a brand now. We have to keep selling our adventures, our thoughts in exchange for likes, views, kudos. We sell facets of our time outdoors, shrinking and aesthetically cleansing ourselves into molds of relatability, trying to one-up others in celebrations of success. ‘The less said about it the better’ feels almost radical in its intent to refuse to repackage your precious time alone with your body, outdoors, seeking adventure.

And yet, herein lies a tension I keep wrestling with, as there usually is whenever I think too much about something, as I am a woman. The age-old conundrum. I am constantly torn by an infatuation with quietly getting on with my life and a societal pull to very openly share my experiences as a woman who takes part in sports still heavily dominated by men. Even now, in 2025, cycling has so few women cyclists that I want to provide myself as a stepping stone into riding for others, if I can. Equally, as a self professed back-of-the-pack runner, the more I talk about how I’m regularly coming in last place in races and events but still really enjoying it, surely serves a much more important purpose than saying nothing? But am I the right person to be talking about my experiences? Who else will talk about them if I don’t? Who does my silence benefit, and what does it say about the sports I love and want to see flourish?

I partially wonder whether some of the interest for Joss in ‘saying nothing’ was the intrigue of hearing other people tell his story, either through words about him, or in the runners who later tried to take on the challenges he had succeeded in. Afterall, humans are just a complex web of stories we tell about ourselves and others, and I don’t doubt that wouldn’t have been lost on Joss. In a lot of ways, the story of Joss Naylor both is - and isn’t - fell running. What fell running became has been shaped by him, and what it could have become has also been shaped by others in his footsteps.

Or maybe, just maybe, by the age of 88 when the interview was conducted, after a lifetime of running hard up hills, he was just absolutely over his own shit, and didn’t want to talk about it anymore.

All I know is that I keep thinking about the wisdom of shutting up, and I’m still working on it.

Very thought-provoking, and I can certainly relate - especially also being a woman in a very male-dominated sport! I feel like I've gone through every iteration of sharing/not sharing my climbing and questioned myself inside-out about it. Do grades matter? Am I sharing this because I like the picture or because I want people to know how hard I've climbed? Does anyone actually care? Am I even climbing this route for the right reason?? I feel like I've finally reached a comfortable balance that I'm happy with and it's definitely on the pared back side. I find myself sharing less and less, and writing for myself - either blog or personal, paper journal more and more. They scratch the itch of getting my thoughts out and sorting through an experience without tying up too much external validation in it (given that only about 5 people read my blog haha). Thanks for this.

Really interesting read. I've never been very sporty or competitive and always been a bit overwhelmed and intimidated by some of the epic adventure and sports stats that litter social media. I think it's important to have balance. I have spent recent years getting into a headspace where I can focus on enjoying the journey - not just feeling like I have to get through it as soon as possible.