Word and movement: Running the red line in Dreamtime Fellrunner

How a one-woman performance on fell running has given me words I've been looking for.

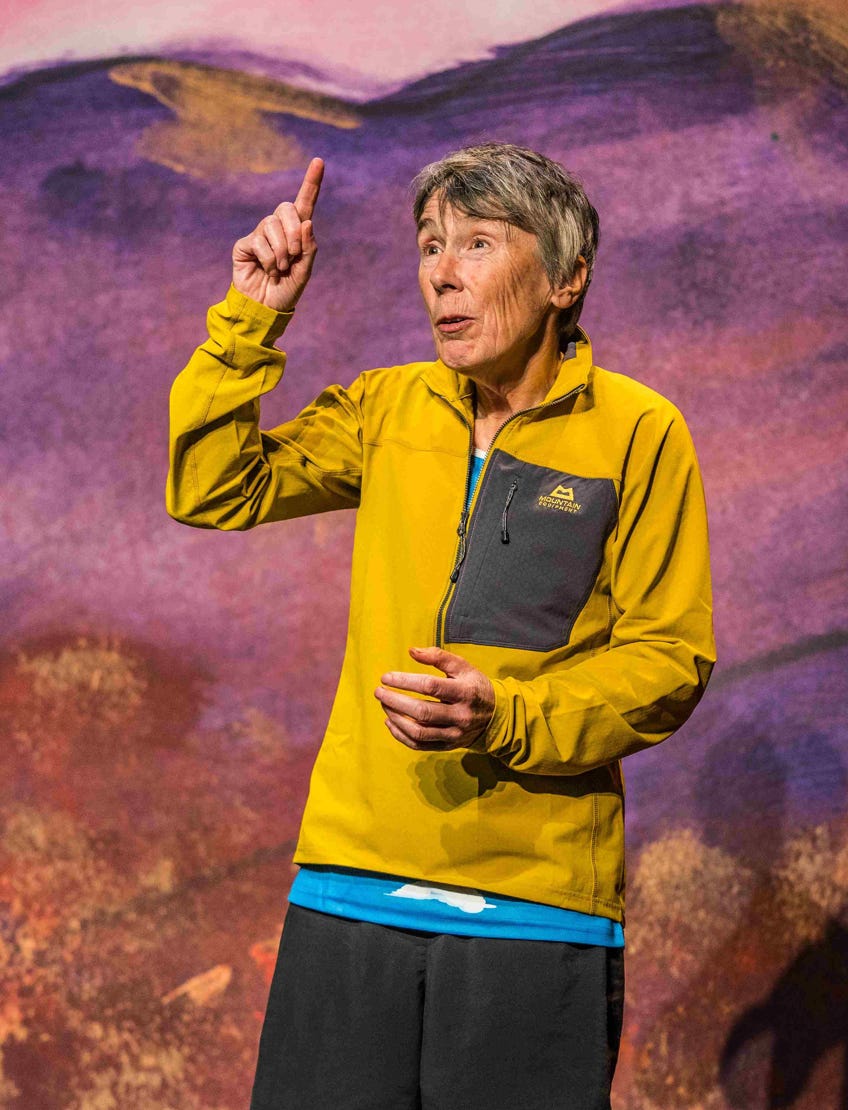

Last night I went to watch a one-woman theatre piece on fell running and toppled head over heels in love with a woman called Jules Carter as she wove a 60 minute spoken word poetry piece about the thin line between running and art. I sat in the front row of the tiny black-walled Garret theatre at the Storyhouse in Chester, with absolutely no expectations, only to find myself spell bound and clinging by my fingernails to the words that tumbled from this small, grey-haired woman.

Jules blazes into the room in the recognisable uniform of a fell runner; bright waterproofs, shorts, lugged-trainers and a beanie hat. The lights flare yellow and then blue, and a recording of lakeland rain washes over the audience as she describes her blood and bones as mud puddles and stones. The audience recoils slightly behind me, I can feel that they’re nervous this will be one of those awful artsy shows where someone will overshare, or force them into audience participation. They’re regretting their £15 ticket already. But as Jules goes on, as the music picks up and she moves through her work, they begin laughing, leaning forward. The wriggling, nervous fidgeting stops. We settled into the Dreamtime Fellrunner.

Dreamtime Fellrunner is one of those things that if I described it to you I don’t think you’d want to go and watch it. I heard as much too from other runners in the interval mingling at the bar: ‘I had no idea what to expect,’ one man says as he swills the dregs of beer in his plastic cup, ‘I can’t believe she can talk like that about running. It’s beautiful.’

The piece is 60 minutes of vulnerable and humorous poetry, where Jules Carter, a fell runner from Keswick, explores everything that has built the story and experience of fell running for her: the history of the sport, the place of the lakes, the people, her body, the pain, the weather, the ableism, misogyny, her own self doubt. It moves rapidly and quickly, her poetry enrapturing and not at all obtuse. There is stage light work and a sprinkling of music. Jules ropes in local running clubs to provide the audience participation we were all dreading, which is funny and a great way of bringing local communities into a moving, flowing piece. Many of us recognise the runners on stage; we’ve run with them, seen them at races and the community events we’re part of. It draws us in. Jules blurs the line between poetry and theatre and her sport. There is no start, there is no end in either. It’s all about how you experience them, and it’s the first time I've ever seen quite such a creative reconstruction of that idea.

Broadly, I am a bit nervous about one-person theatre pieces. I am also nervous about art pieces that try to bring sport and artistry together. In both cases they can come across too contrived or overly vulnerable that it makes it a challenging watch. This, however, was neither.

Jules is still touring, so I won’t spoil it for anyone who wants to go and see it, but I will pick out some of the themes that resonated with me. It’s an art piece that I think will stay with me for a long time.

The poetry of movement

‘A poem is only a poem if you can feel it,’ Jules says. This is the crux of this theatre piece. It’s an experiment in drawing the two together and getting you to feel it too, by imposing your own experiences on her words. She describes her process of running and writing as one in the same: both are created outdoors and utilising her body to build them. At one point she re-enacts the process of physically picking up words as if they’re stones on her path up the fell, turning each one over, considering their placement, their shape, their sound and how they feel in her hands. ‘Do not cast words out into nothingness’, she calls, before holding an odd-shaped word ‘fear’ and questioning where it sits in her body.

Oh. My. God.

These are themes that I have been rankling with for years. Running, cycling, climbing, and swimming all provide a creative outlet for me in ways sitting in front of a notebook or at a desk with a blank page can’t offer. It’s a partial reason why recording my sessions on strava has always been a bit redundant. Ok, I can tell you my mileage and distance and speed, but what does that say about me? Do you know anything more about how I've felt or thought or what I’ve seen based on those metrics? No. I’ve spent my life writing documents about my achievements, how I have met targets, how I am going to approach goals - when I leave the office and step out into the wide expanse of the evening air, I don’t want any of that.

Jules says she can start a run and end it with a fully formed poem in her mind. My mind doesn’t work like that, not during running anyway, where my whirring, clicking brain finally, joyfully, sinks into a white haze of quietness. Occasionally, I’ve finished a run slightly disoriented; where Jules would have stanzas and iambic pentameter, I instead feel like I’ve been wrenched from the belly button back into reality. It takes a moment for life to slide back into place.

For me, cycling is my most creative act. I don’t know what it is about the rhythmic movement of the pedal strokes, but it is in a saddle that I can finally churn my thoughts into the silky butter and i’ll be able to articulate the things I want to say. Occasionally little seeds of things I want to write will land in my palm, and I’ll be able to grow them over time; at other moments I’ll be tasting words and sentences on the tip of my tongue as I cycle through green, and gold and bronze. Frozen fingers, and cold nosed, clear breathed, dew soaked hedges and frothing elderflower, and I’ll want to pull words to describe it all.

Because how can movement be anything other than art? How can we possibly have this impossible body, that can move and reflect and conjure language and words and build connections and see a spectrum of colour and light and for that experience to not be art? How can we weave through a landscape that has been shaped by movement much larger and more inconceivable by us, honed by consequence and the choice of other’s stories and not feel our own melded to it in some strange way? How can that be anything other than poetry?

Body

Her body as a vehicle for artistry and running, it is inevitable that Jules would bring this to the fore. Jules has a slight spinal deformity that gives her a hunch and she describes in detail the pain it causes in running, her awkward mechanics and how taunts from other children and adults in her life shaped her perspective. ‘If I am going to be in pain,’ she says as she leaps up boxes, ‘then let it be for a purpose’. Her purpose, of course, is not to be ‘the right shape’, but instead to experience the world through her feet and her hands and her movement. ‘Pain’, then, becomes part of the rich tapestry of her life that she, herself, has not just carded the wool for, but hand picked, embroidered, considered. Pain is not the tapestry, but the complex weave of the thread, amongst thousands of other threads.

To hear Jules talk about her body was liberating for a mind like mine that has spent nearly 25 years hating her own. ‘Running doesn’t care for your body type,’ she says. And she’s right. It’s not even that profound of a wording, she is literally objectively correct. Every week I diligently turn up to park run at my local forest, surrounded by 500 others with every conceivable body type under the sun, jostling for a place and position. I am over taken by men and women older and younger than me, bigger and smaller than me, taller and shorter than me, and in some cases, more or less limbs than me. Hating my body and the way I move has got me absolutely nowhere. It has neither improved my experience of, nor my ability to contribute to a sport I have loved since I was 15 years old. And this feeling, these reflections, continue to tumble in my mind as Jules speaks.

The history of running

The legend that he was, of course Jules brings up her brief friendship with Joss Naylor. I wrote a substack on some of his words a while back if you recall, and was pleased that my encapsulation of him wasn’t completely off. In the Q and A section, an audience member asked about her relationship with him and what he was really like. ‘He had a kind word for everyone,’ she said, ‘he was much more interested in you, had time for everyone and believed if you had any kind of influence at all, you have a duty to use it to make the world better for others.’ Personally, if something of a similar sentiment can truthfully be said about me after I die, then I’ve fully succeeded in my life. No questions asked. It certainly beats an awful funeral I went to last summer, where the only good thing the eulogist could come up with about the person was that they ‘paid their debts on time’.

The mother mountain

Over the years I’ve become more and more fascinated by the stories of older women, who exist in a very specific context - often ignored and marginalised. I don’t have a mum - or at least, I have a biological mum but not a mother I suppose - and so I’ve found that I have begun to seek out the experiences of women who have cut and weeded the paths so that I can more freely saunter my way down them.

Jules speaks of her ‘mother mountains’ who guide her way, not quite knowing that she herself is becoming mother mountain to others.

Damn Jules, thanks for giving me the words I have been trying to find.

To find out more about Jules and where you can watch this piece, please go to > https://www.mindfell.co.uk/events

I was sad to have missed this. It sounds like it was quite a profound little evening. I especially love the Mother Mountain part of your write up, I am now rather misty-eyed :)

I know Jules! She's brilliant. I didn't know she was touring with this and it's a shame I missed it as I'm close to Chester, I wonder if I can catch her elsewhere. I'm glad you enjoyed it!

I fully agree with what you said about older women - I am incredibly lucky to be a part of a community - the climbing club I talked briefly about in my most recent post - that spans an age range of mid-20s to 100 years old and I feel a deep awe and inspiration for these older women who have lead these incredibly rich and exciting lives. I want to learn everything from them. I want to sit on the floor and listen for hours while they tell me their stories. I wish that every young woman could find her equivalent. Good luck finding your mother mountains!